The Federal Reserve's policy response to the latest financial crisis can be summed up in one word: unconventional. Between interest on excess reserves (IOER), quantitative easing (QE), and purchases of mortgage backed securities (MBS), the Fed has deployed a wide range of instruments to avoid deflation while preserving financial stability. However, although it is clear the Fed has acted in many ways, what is still unclear is how these policies impact the financial sector and the economy at large. Is interest on excess reserves expansionary or contractionary? Are large scale asset purchases expansionary or contractionary? A rapidly growing and evolving shadow banking sector has only worsened this confusion, and this post is an attempt to make some sense of these arguments in an illustrated form.

First, an introduction to the major players. Interest on Excess Reserves (IOER) originally was a policy implemented by the Federal Reserve in the depths of the financial crisis to expand the Fed's balance sheet to ease liquidity needs. It authorized the Federal Reserve to pay banks interest on their reserves that were in excess of the required amount, and thus gave all commercial banks a risk free return of 0.25% on any extra available cash. However, as a side effect, it meant that banks were unwilling to invest in any security that had a nominal yield of less than 0.25%, as they could just plow that money into excess reserves instead.

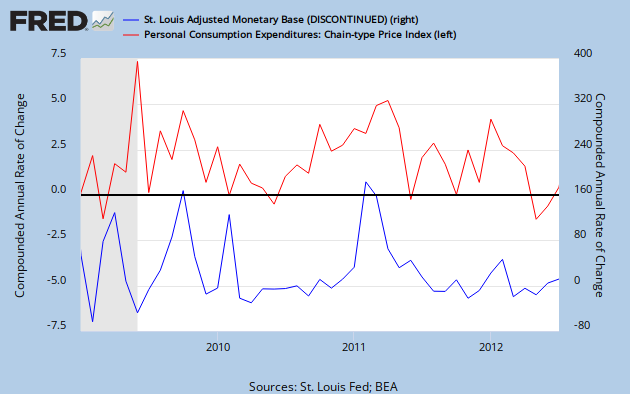

IOER was especially important in limiting the inflationary effects of the Fed's Large Scale Asset Purchases. In these programs, the Fed massively expanded its balance sheet by purchasing either long-term treasuries (QEI, QEII), or mortgage backed securities. These purchases have more than tripled the Fed's stock of treasuries from about $480 billion in August of 2008 to $1.64 trillion in August of 2012, raising the monetary base from $884 billion to about $2.61 trillion in the same time period.

These purchases of treasuries have been problematic for the shadow banking sector, notably the oft maligned money market funds, as the purchases have drained the financial system of safe collateral. Money market funds offer a liquid, yet interest bearing fund for large deposits by taking the deposited cash and entering into repurchase agreements, or repos. Repo is a sort of rental arrangement in which the money market fund "rents" out its cash to firms who need liquidity but who do not want to sell their assets. A typical repo involves the money market fund giving another investor cash in exchange for an asset, then after a certain period of time, the investor repurchases the asset and the money market fund gets its cash back with an interest payment. However, the lower the yield on the underlying asset, the smaller the interest rate payment. As a result of the financial crisis' effect on the perceived riskiness of "unsafe" assets, treasuries have become the asset of choice for repos. However, the shortage of safe collateral has pushed down yields on treasuries. As a result, money market funds are surviving on smaller and smaller spreads, putting them in a precarious position and threatening a contraction of collateral chains. The fear is that if this continues, money market funds will collapse and a (shadow) bank run will cause a liquidity and solvency crisis.

This new element of shadow banking makes evaluating monetary policy a headache. Traditionally, expansionary monetary policy in the form of asset purchases works like in the diagram below. When the Fed buys assets, the money that it injects into the market goes to commercial banks who can then lend out the money and make a yield. Also, the market for treasuries doesn't shift that much as banks can also sell their holdings of treasuries, preserving the model of the shadow banks as they can still make some yield off the repo agreement.

However, in the current crisis position, the situation is very different. Because of the safe asset shortage, commercial banks pile into treasuries as a way of getting some yield for their depositors. This is happening at the same time as the central bank buys large stocks of treasuries, thereby contracting the supply of treasuries even further. As a result of high treasury prices, shadow banks struggle as they can no longer provide a sufficient yield. Commercial banks are in a better position than shadow banks because commercial banks can still park their excess reserves at the Fed and earn IOER. They can limit their purchases of treasuries, thus maintaining what is left of the treasury market.

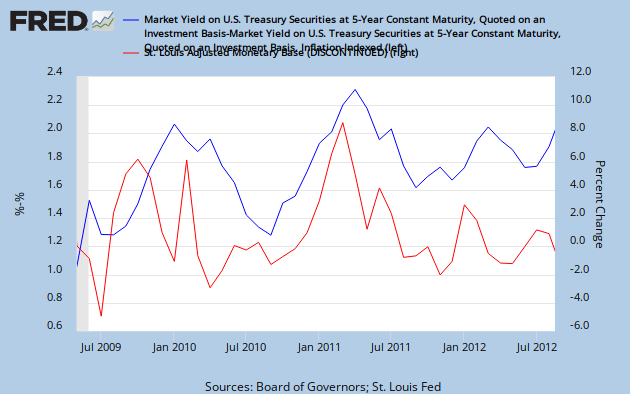

The key question that David Beckworth and Cardiff Garcia are trying to settle is what would removing IOER from the system do? David Beckworth focuses on the money side, and argues that a removal of IOER would be seen as a permanent expansion of the monetary base, thereby rapidly boosting inflation expectations. In response, banks sell off treasuries and invest in riskier assets which keeps shadow banks safe. His world looks much like the following picture:

On the other hand, Garcia focuses on credit, and argues that IOER is the only thing keeping treasury interest rates positive. Therefore a removal of IOER would lead to massive expansion of commercial bank purchases of treasuries in search of yield, thereby collapsing the shadow banking sector as the system is drained of safe collateral. His world looks much like the picture below:

The critical difference between the two scenarios is how IOER affects commercial bank purchases of treasuries. Beckworth seems to believe a removal of IOER would push banks into riskier assets, thus causing banks to sell treasuries and keep shadow banks safe. On the other hand, Garcia seems to believe a removal of IOER would not be enough to compensate for the perceived riskiness of non-treasury assets, so banks would purchase treasuries in response to a cut in IOER. This would contract the supply of treasuries, destroying the shadow banking sector.

So which one is correct? To be honest, I don't know for sure, and I'm not sure if either Garcia or Beckworth can be certain about the whole story. But Dan Carrol mentions an interesting option that would perform well in spite of this model uncertainty: sterilized lowering of IOER. In this case, the Fed removes IOER, but then partially compensates for the treasuries bought by commercial banks by selling its own stock of treasuries. The drawing looks something like this:

This might seem counter intuitive as the central bank appears to be doing two actions that seem to contradict each other. Yet if we consider the role of expectations, such a policy becomes much more logical. Given that the monetary base has more than tripled since 2008, it should be clear that the market does not expect that expansion to be permanent. According to Krugman, a fully credible expansion of the monetary base in this period and all future periods should directly lead to inflation. Therefore, since prices have not tripled in response to the change in the base, markets must be pricing in the fact that the base expansion will be sterilized by the Fed in the future.

To raise inflation expectations, the Fed must credibly commit to a future base expansion, and, paradoxically, it cannot do so if the monetary base is too large. Therefore, if sterilized IOER reduction is seen as a move to hitting a nominal target, such as higher NGDP, it can still be part of a credible package that restores the nominal target while preserving the shadow banking sector. In the case of NGDP, a rough estimate of pre-crisis trend growth puts desired NGDP at about $17.3 trillion, about $1.7 trillion dollars above where we are now. Because the average NGDP to Monetary Base ratio over the Great Moderation was about 16.3, a reasonable monetary base would be about $1.06 trillion, $1.59 trillion less than the current monetary base. This means as long as the Fed can credibly commit to permanently expanding the monetary base to around $1.06 trillion, the Fed has room to unwind about $1.59 trillion of treasuries. This would expand the supply of safe collateral and address Garcia's concerns. In addition, giving up on IOER and credibly committing to a permanent base expansion would address Beckworth's call for a regime shift that would restore trend NGDP growth.

A sterilized reduction in IOER would have other advantages as well. First, because its mechanism is not dependent on central bank treasury purchases, there's no risk that shadow banking troubles would lower NGDP growth. Since there's uncertainty about which of Garcia's or Beckworth's scenario would play out, an unsterilized reduction in IOER would translate into uncertainty about whether future NGDP growth should go up or down. Markets would still be uncertain on the status of the shadow banking sector, thus holding back growth.

Second, sterilized cuts in IOER directly commit to a modest increase in the monetary base instead of relying on small monetary frictions. One argument for LSAP's effects on expectations is that an increase in the Fed's balance sheet increases the fraction of its balance sheet expansion that markets expect to be permanent. In other words, the expected future monetary base is convex with respect to the current monetary base. But this approach is fraught with uncertainty and a lack of precision, which may be an issue holding back further monetary easing. If the set of possible inflation rates are {1, 1,2, 1.4, 1.8, 2, 10, 100}, this may change whether the central bank is willing to ease or not. Unwinding the balance sheet while cutting IOER would increase the Fed's precision, improving monetary credibility.

Another framework in which sterilized IOER makes sense is DeLong's law, a modification of Say's law and Walras' law. Say's Law originally said that excess demands for all goods must add up to zero, so there cannot be a general glut.

(equations from Mark Thoma)

However, Walras pointed out that we needed to include money in this model, therefore there can be a general glut in goods if there is excess demand for money. This opens up a role for monetary policy to reduce that excess demand.

DeLong then argues that another factor we need to be aware of in the recent recession is excess demand for safe assets. So Walras' Law should be expanded further:

This framework clearly delineates between what Beckworth, Garcia, and Carrol are proposing. Beckworth argues that lowering IOER directly solves excess demand for money, and therefore goes on to solve excess demand for safe assets. But Garcia argues lowering IOER directly increases excess demand for safe assets to such an extent that it overwhelms any reduction in excess demand for money. So while directly cutting IOER reduces excess demand for money, it's ambiguous whether it reduces the general glut for goods. Carrol's proposal then comes in the middle, as cutting IOER reduces excess demand in money while sterilization reduces excess demand for safe assets.

In the end, this debate shows not only why the market monetarist focus on expectations is important, but also why an analysis of mechanisms cannot be ignored. All of these arguments for sterilized IOER depend on a credible commitment to expand the monetary base, so if the market expects the Fed to maintain a 2% inflation ceiling the policy change would still be useless. However, changing the target without being aware of the collateralized world we live in would also be a failure, as we would be twisting the dials in all the wrong directions, endangering monetary credibility.