Intellectual honesty means disagreeing with even those who are “on my side”. So when the arguments I have made against Reaching for Yield are also arguments against doomsday predictions for the taper, I have to speak up.

In this case, I have Brad DeLong in mind. In a post today, Brad sees the recent rise in real interest rates as measured by the 10 Year TIPS yield and the fall in inflation expectations as measured by the 10 year breakeven as cause for alarm, claiming that “Not since 1991 have we had such a large and rapid contractionary shift in the market's belief about what the Federal Reserve's reaction function.”

Reading his post, it almost sounds like Fed policy is going to collapse growth. But I would argue that while Fed policy is failing to promote maximum employment, it hardly follows that growth will collapse. I come to this conclusion also by looking at financial data. Below I reproduce a plot of the real interest rate, inflation breakeven (both 10 year), and add a plot of the SP500. I focus in on 2013 to see the recent dramatic changes.

We can make some stylized observations. First, the real interest rate has been on a steady rise since May. Second, the inflation breakeven has been on secular decline since about March. Third, in spite of all of this, the SP500 has been steadily growing, rising more than 10% on a year to date basis.

How should we interpret this? If we accept the uncontroversial proposition that stock market movements reflect expectations of future growth, it should be clear that the fall in inflation expectations does not reflect a fall in expected future nominal GDP. This is a break from the trends from 2010 to 2012. But if inflation is not moving in the same direction in output, it must be that a positive supply shock is the driving factor behind the fall in inflation breakevens.

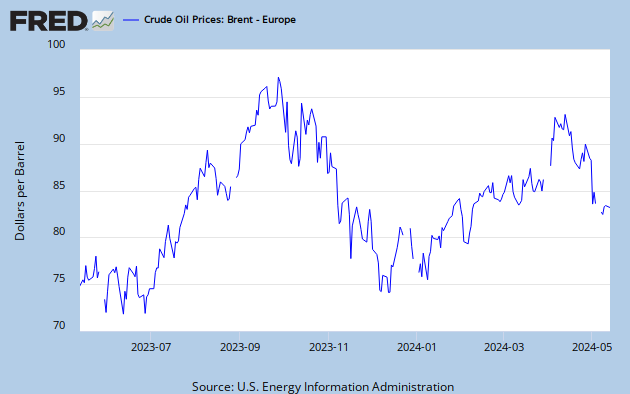

The natural candidate for the positive supply shock is the fall in oil prices. The recent slowdown in emerging markets and massive expansion in oil production has lowered energy costs for the United States. This is a textbook expansion in aggregate supply, and we should naturally expect output to rise, inflation to fall -- precisely what we observe above.

Nonetheless, I still agree that more monetary stimulus is desired. To see this, we should consider the first differences in inflation expectations and the SP500. In the plot below, I have plotted weekly percent changes in the inflation breakeven and the SP500. Blue denotes points in the 2010-2012 time period, and red denotes the points on a year to date basis. Note that in both samples there is a positive relationship between changes in inflation expectations and changes in the SP500. However, the year to date group has a higher intercept, reflecting that the SP500 has shifted to a higher trend growth path relative to the 2010-2012 period. Indeed, if you run the regressions on the first differences, you find that in the 2010-2012 period, the SP500 would gain only 0.23% in a week if inflation expectations were unchanged. However, in 2013, the value is 0.76% -- almost triple what the previous trend growth rate.

These facts show the simplest version of the aggregate supply/aggregate demand model in action. If inflation falls while nominal GDP rises, then it must be a positive supply shock. For every level of inflation we achieve a higher level of output. But even after the positive supply shock, aggregate demand policy still plays a role -- i.e. any marginal rise in inflation still translates to a rise in output.

What went wrong in DeLong’s original analysis was that he reasoned from a price change. He started by talking about inflation and interest rates and then translated that into a statement about monetary policy. On the other hand, I started with a quantity -- the SP500 -- and used that to interpret the price changes. This allows me to fit the data into the standard AS/AD model.

I can then break down potential data changes to events in the AS/AD model. DeLong writes out a list of four possibilities to interpret changes in the real interest rate and the inflation breakeven. II have produced a similar table below that translate the AS/AD arguments I made above. My version provides endogenous predictions for the real interest rate -- the market indicators are inflation expectations and the SP500.

In my view, the economy is in state (4). Inflation is weak, but growth will be strong. These growth prospects are also corroborated by the relative strength of cyclical stock sectors relative to safe ones. Investors are ramping up -- not buckling down -- as expectations of future nominal GDP rise. Bottom line? The taper isn't going to knock growth far off track.

This rate story shows how important markets are in market monetarism, TIPS spreads and movements in the SP500 make for an easy breakdown of aggregate supply aggregate demand. We should take them seriously, even if it’s politically inconvenient for those of us arguing for monetary easing. Interest rate movements signal changes in the reactions of the Fed. But since it's unlikely that the Fed will screw up so badly so as to have elevated interest rates for an extended period when the economy is suffering, rising long rates almost always indicate higher expected nominal GDP. These financial indicators provide policy makers with forward looking data on which to base policy -- a cornerstone of market monetarism.

I want to end on what the above means for monetary policy and advocates of monetary easing, such as myself.

First, the recent fall in inflation breakevens should not be interpreted as a monetary tightening -- the change is not being driven by demand, but rather by supply. Second, the Fed is severely failing its dual mandate. Now that inflation is falling, the Fed should have even more latitude to pursue its full employment objectives. In this light, the taper is madness. Third, advocacy for monetary easing should focus on the human costs, not financial costs, of tight money. Wall Street will move on, but Fed complacency in the face of half a decade of slow job growth will leave scars on Main Street for years to come.

I disagree on a few things:

ReplyDelete(1) The idea that this is a supply shock. I did an analysis recently that looked at where the disinflation was happening. I found it was in basically every category of consumption and investment good. That seems to fit the story of demand shock rather than supply shock.

A little more on this: I'm befuddled by your use of Brent. You should be looking at West Texas Intermediate for US oil prices. Also, the timing of the drop doesn't fit for inflation expectations. If you look at daily WTI data, you'll notice we're up sharply over the last month. Natural gas prices have also risen in the relevant time interval. Weekly average national prices for regular gasoline are roughly stable.

I just don't find the supply shock story compelling in the least, sorry. I don't see where it is, yet I see the obvious marginal deflationary impact of the accelerated taper.

(2) I refer you to my prior analysis of the rolling correlation coefficients. That convinced me that increases in real interest rates are now associated with less growth, rather than more.

(3) I'd also question the usefulness of the stock market here as a level indicator. Last I checked, its performance hasn't been matched by employment or output. You'll notice, too, that the IMF dropped its global and US growth forecasts yesterday with an explicit mention of the Fed's exit.

Evan,

Delete1. Even if every category has a disinflation, it can still be a supply shock. I don't remember any accounting for sectoral growth in the textbook AS/AD model, so I fail to understand why a general disinflation is only consistent with a demand, not supply, story.

If we want to talk about sectors, I would argue that the between sector performance shifts in the stock market point towards stronger growth. Since cyclicals are outperforming defensive sectors, this shows that people see the future economic environment as improving.

Before I address the timing issues, note that we have an identification problem here. Suppose that both AS and AD shocks are happening. Then it's entirely possible to see the price of oil rise, inflation breakevens fall, and the stock market slip, even though an AS shock has occurred. How do we identify the AS shock then? I would argue my second scatter plot does that. It shows that at every level of expected inflation, expected future nominal growth is higher. Even if you disagree on the cause of the supply shock, this structural shift in regression lines is the smoking gun of an AS shock that we are looking for.

On the specifics, I use Brent because want to illustrate the prospect for a global increase in oil production. What really matters for a supply shock isn't the day to day price of crude or gasoline, but changes in the global production possibilities frontier for oil. U.S. crude production has risen by almost 50% over the last five years. We've become the largest exporter of refined fuels [http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-07-10/fracking-pushes-u-s-oil-output-to-highest-since-january-1992.html]. Recent discoveries of natural gas in the U.K. and interest in all the oil coming out of Eagle Ford [http://www.google.com/trends/explore?q=eagle+ford#q=eagle%20ford&cmpt=q] are all reasons for why the AS shock would show up in the data now, and not before.

2. On the rolling coefficients, see the identification problem above.

3. Perhaps the stock market may not perfectly correspond with nominal GDP, it is arguably our best high frequency measure of expected nominal GDP. Even in a world of "ketchup economics", the inflation/output forecasts that arise from financial data should be consistent. With this, we see the identifying mark of an AS shock.

Look, the point isn't to say we don't need monetary easing, or that an AS shock will save us from a reckless Fed. But growth isn't going to fall off a cliff, and I don't think it helps the credibility of market monetarists to look at the financial data and say that it will.

"If we want to talk about sectors, I would argue that the between sector performance shifts in the stock market point towards stronger growth. Since cyclicals are outperforming defensive sectors, this shows that people see the future economic environment as improving."

DeleteNot necessarily. It could be position away (bidding down of) from bond-like dividend paying equity sectors that are typically defensive in nature and not so much a move in favor of cyclicals. This would make sense as nominal rates on fixed income rise.

Also, if the move in real interest rates are a result of a demand shock that happened to begin around May/June, it could be that a major source of demand from the system has been reduced. Wonder what that could be?

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/us-posts-117-billion-june-budget-surplus-2013-07-11

Two points.

DeleteFirst, I think Harless' analysis shows that this isn't true. With the risk free rate rising, this means stock price increases signal even stronger expectations of future cash flows.

http://blog.andyharless.com/2013/07/taper-paradox.html

You can also think of the problem as a return on equity problem. Suppose future growth expectations have fallen. By definition, the return on a stock should equal the risk free rate plus the equity risk premium. Recent treasury moves have shown that the risk free rate has risen. What do we think should have happened to the equity risk premium? If growth will fall in the future, it should be a safe assumption to say that the equity risk premium has risen. Therefore the expected return on equity has risen.

Now consider the future price. Then if bad growth prospects have sent down the future expected price, the current price must have fallen to satisfy the higher return on equity. Contradiction. We can then conclude growth prospects have risen.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete